In late August 1918, military ships departed the English port city of Plymouth carrying troops unknowingly infected with this new, far deadlier strain of Spanish flu. As these ships arrived in cities like Brest in France, Boston in the United States and Freetown in West Africa, the second wave of the global pandemic began.

“The rapid movement of soldiers around the globe was a major spreader of the disease,” says James Harris, a historian at Ohio State University who studies both infectious disease and World War I. “The entire military-industrial complex of moving lots of men and material in crowded conditions was certainly a huge contributing factor in the ways the pandemic spread.”

The 1918 Flu Pandemic Death Toll Affected All Age Groups

From September through November of 1918, the death rate from the Spanish flu skyrocketed. In the United States alone, 195,000 Americans died from the Spanish flu in just the month of October. And unlike a normal seasonal flu, which mostly claims victims among the very young and very old, the second wave of the Spanish flu exhibited what’s called a “W curve”—high numbers of deaths among the young and old, but also a huge spike in the middle composed of otherwise healthy 25- to 35-year-olds in the prime of their life.

“That really freaked out the medical establishment, that there was this atypical spike in the middle of the W,” says Harris.

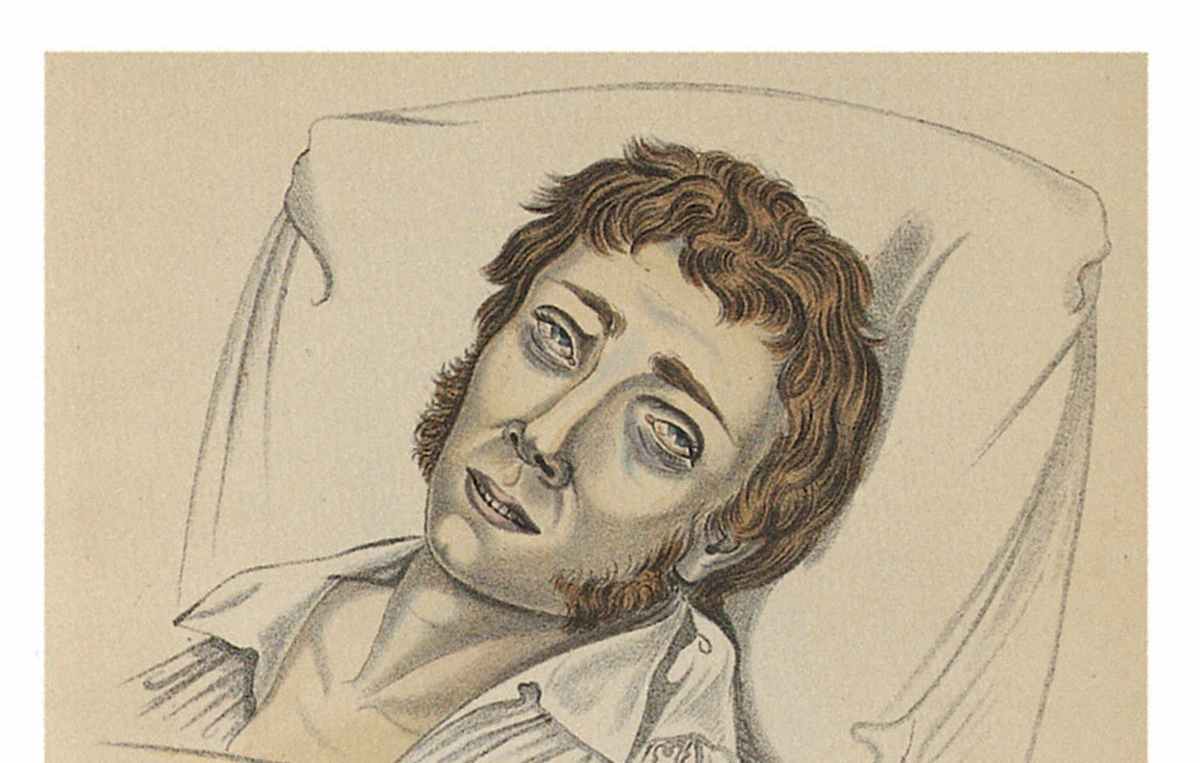

Not only was it shocking that healthy young men and women were dying by the millions worldwide, but it was also how they were dying. Struck with blistering fevers, nasal hemorrhaging and pneumonia, the patients would drown in their own fluid-filled lungs.

Only decades later were scientists able to explain the phenomenon now known as “cytokine storm.” When the human body is being attacked by a virus, the immune system sends messenger proteins called cytokines to promote helpful inflammation. But some strains of the flu, particularly the H1N1 strain responsible for the Spanish flu outbreak, can trigger a dangerous immune overreaction in healthy individuals. In those cases, the body is overloaded with cytokines leading to severe inflammation and the fatal buildup of fluid in the lungs.

British military doctors conducting autopsies on soldiers killed by this second wave of the Spanish flu described the heavy damage to the lungs as akin to the effects of chemical warfare.