With no cure for the flu, many doctors prescribed medication that they felt would alleviate symptoms… including aspirin, which had been trademarked by Bayer in 1899—a patent that expired in 1917, meaning new companies were able to produce the drug during the Spanish Flu epidemic.

Before the spike in deaths attributed to the Spanish Flu in 1918, the U.S. Surgeon General, Navy and the Journal of the American Medical Association had all recommended the use of aspirin. Medical professionals advised patients to take up to 30 grams per day, a dose now known to be toxic. (For comparison’s sake, the medical consensus today is that doses above four grams are unsafe.) Symptoms of aspirin poisoning include hyperventilation and pulmonary edema, or the buildup of fluid in the lungs, and it’s now believed that many of the October deaths were actually caused or hastened by aspirin poisoning.

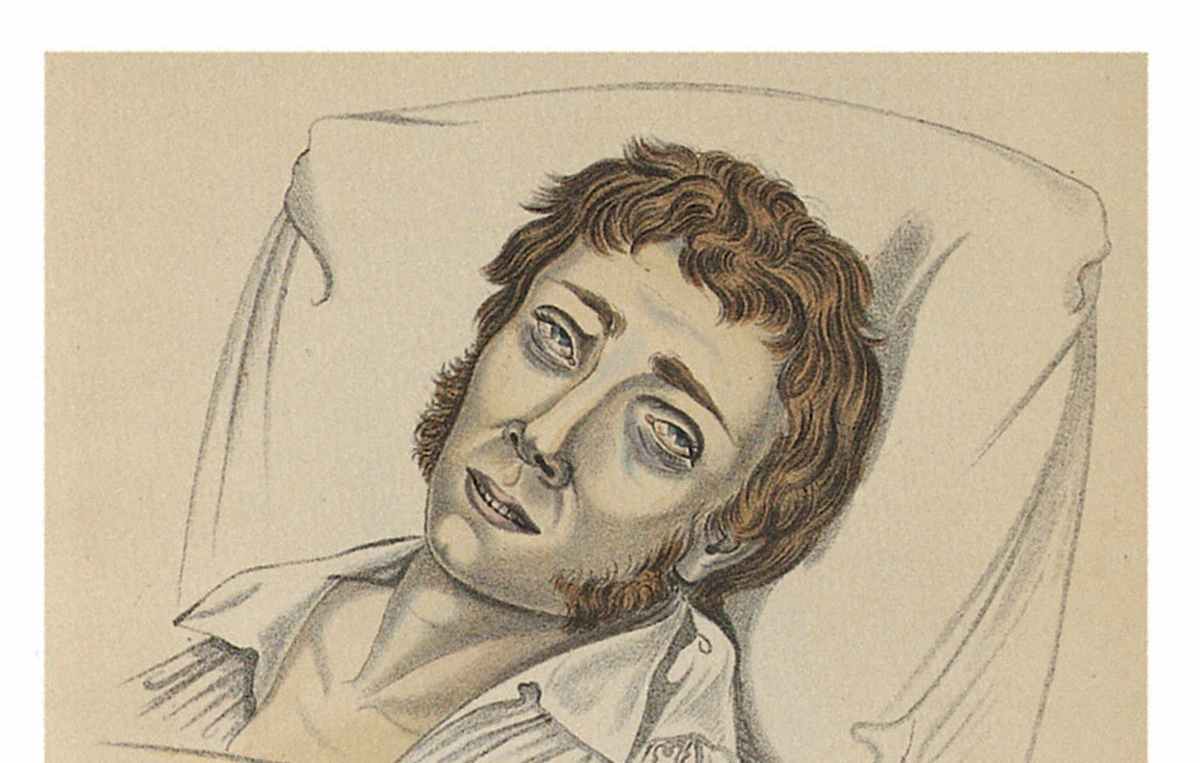

The Flu Takes Heavy Toll on Society

The flu took a heavy human toll, wiping out entire families and leaving countless widows and orphans in its wake. Funeral parlors were overwhelmed and bodies piled up. Many people had to dig graves for their own family members.

The flu was also detrimental to the economy. In the United States, businesses were forced to shut down because so many employees were sick. Basic services such as mail delivery and garbage collection were hindered due to flu-stricken workers.

In some places there weren’t enough farm workers to harvest crops. Even state and local health departments closed for business, hampering efforts to chronicle the spread of the 1918 flu and provide the public with answers about it.

How U.S. Cities Tried to Stop The 1918 Flu Pandemic

A devastating second wave of the Spanish Flu hit American shores in the summer of 1918, as returning soldiers infected with the disease spread it to the general population—especially in densely-crowded cities. Without a vaccine or approved treatment plan, it fell to local mayors and healthy officials to improvise plans to safeguard the safety of their citizens. With pressure to appear patriotic during wartime and with a censored media downplaying the disease’s spread, many made tragic decisions.

Philadelphia’s response was too little, too late. Dr. Wilmer Krusen, director of Public Health and Charities for the city, insisted mounting fatalities were not the “Spanish flu,” but rather just the normal flu. So on September 28, the city went forward with a Liberty Loan parade attended by tens of thousands of Philadelphians, spreading the disease like wildfire. In just 10 days, over 1,000 Philadelphians were dead, with another 200,000 sick. Only then did the city close saloons and theaters. By March 1919, over 15,000 citizens of Philadelphia had lost their lives.

St. Louis, Missouri, was different: Schools and movie theaters closed and public gatherings were banned. Consequently, the peak mortality rate in St. Louis was just one-eighth of Philadelphia’s death rate during the peak of the pandemic.

Citizens in San Francisco were fined $5—a significant sum at the time—if they were caught in public without masks and charged with disturbing the peace.

Spanish Flu Pandemic Ends

By the summer of 1919, the flu pandemic came to an end, as those that were infected either died or developed immunity.

Almost 90 years later, in 2008, researchers announced they’d discovered what made the 1918 flu so deadly: A group of three genes enabled the virus to weaken a victim’s bronchial tubes and lungs and clear the way for bacterial pneumonia.

Since 1918, there have been several other influenza pandemics, although none as deadly. A flu pandemic from 1957 to 1958 killed around 2 million people worldwide, including some 70,000 people in the United States, and a pandemic from 1968 to 1969 killed approximately 1 million people, including some 34,000 Americans.

More than 12,000 Americans perished during the H1N1 (or “swine flu”) pandemic that occurred from 2009 to 2010. The COVID-19 pandemic, which started in December 2019, spread around the world before an effective COVID-19 vaccine was made available in December 2020. By May of 2023, when the World Health Organization declared an end to the global coronavirus emergency, almost 7 million people had died of COVID-19.

Each of these modern day pandemics brings renewed interest in and attention to the Spanish Flu, or “forgotten pandemic,” so-named because its spread was overshadowed by the deadliness of World War I and covered up by news blackouts and poor record-keeping.

Sources

What the Spanish Flu Debacle Can Teach Us About Coronavirus. Politico.

WHO declares end to Covid global health emergency. NBC News.